|

|

|

|

August 30, 2012

Creators Syndicate

Once a year, I gather with four colleagues in Paso Robles, the heart of

California's vast Central Coast, to judge the culinary entries at the annual

Winemakers' Cookoff, which benefits the local Rotary's scholarship fund.

This year's event was the 14th, and it was Americana in its purest form.

Smoke from a couple of dozen grills — in the Central Coast that means mobile

Santa Maria barbecue pits — wafted through a crowd of more than 1,000, as a

country-rock band played on a stage at the edge of a nearby lake.

The day had been a scorcher, with the mercury soaring to 108 degrees,

and the dress for the evening event was decidedly cowboy casual. The rules of

the Winemakers' Cookoff are simple. Each entry's core ingredient must be cooked

on the grill, and a winery principal must be a member of the grill team. The day had been a scorcher, with the mercury soaring to 108 degrees,

and the dress for the evening event was decidedly cowboy casual. The rules of

the Winemakers' Cookoff are simple. Each entry's core ingredient must be cooked

on the grill, and a winery principal must be a member of the grill team.

My qualifications for judging are equally simple. I am an avid grillmeister

and determined advocate for barbecue-friendly wines.

As such, there are three days a year that are sacred to my pursuit of the

perfect grilling wines: Memorial Day, the Fourth of July and Labor Day. As I

pondered the merits of each savory dish that passed my lips at the Winemakers'

Cookoff, I couldn't help but be reminded that Labor Day is near and I must soon

get my own menu in order.

First, however, I must select the wines. This is my favorite part of

grilling.

As you might imagine, the wine flowed at the Winemakers' Cookoff. At the

beginning, while the sun was still up, the thought of a bold red wine, any bold

red wine, was anything but appealing.

I went looking for a well-chilled rose and found two that I enjoyed

very much, the Eberle 2010 Syrah Rose and the Penman Springs 2010 Syrah Rose.

Both were crisp and refreshing, completely dry, with plenty of spicy fruit. Both

are from Paso Robles, of course, and might be difficult to source in your

neighborhood. I went looking for a well-chilled rose and found two that I enjoyed

very much, the Eberle 2010 Syrah Rose and the Penman Springs 2010 Syrah Rose.

Both were crisp and refreshing, completely dry, with plenty of spicy fruit. Both

are from Paso Robles, of course, and might be difficult to source in your

neighborhood.

Nevertheless, rose on a warm grilling day should be a staple for every

grillmeister not predisposed to a cold beer, instead. A common myth about rose,

or what many call "pink" wines, is that they are icky sweet and not compatible

with savory cuisine.

There are rose wines that certainly fit that description, and there is

nothing wrong with enjoying a sweet rose.

But dry rose is the better fit

for most palates when paired with smoked meats, grilled seafood or spicy fare

from the barby.

Depending on your location, you might find delicious rosado from Spain's

Navarra or Rioja regions or tasty rosato from Italy. And there is always rose

from the south of France, regions such as Bandol or Tavel, where sipping rose on

a muggy summer day is almost a religion.

No matter what I say about the virtues of rose, however, someone in the crowd

will ask for a white wine, instead. I will be prepared.

I plan to offer up three levels of white wine: a steely, mineral-driven

gruner veltliner from Zocker, made from grapes grown in California's Edna

Valley; a luscious albarino from Paco & Lola, a top-notch producer in

Spain's Rias Baixas region; and the full-bodied Chablis Saint-Martin from

Domaine Laroche in Burgundy.

All three are award-winning wines that have impressed me in

tastings over the course of this year. They also have the added benefit of being

relatively low in alcohol (well below the seemingly standard 14.5 percent), and

they're value-priced at about $20 — a good price considering the quality in the

bottle. All three are award-winning wines that have impressed me in

tastings over the course of this year. They also have the added benefit of being

relatively low in alcohol (well below the seemingly standard 14.5 percent), and

they're value-priced at about $20 — a good price considering the quality in the

bottle.

Again, depending upon where you live, you may not be able to obtain all or

even any of those three, but style is more important than brand in the grilling

experience. Avoid fat, oaky chardonnay. Go for whites that offer good complexity

without being heavy or high in alcohol.

That's where having a knowledgeable wine merchant becomes a tremendous asset.

Don't be afraid to ask what you might think is a dumb question. It's your money.

My top red for this Labor Day is from Portugal. It is the 2007 Pombal do

Vesuvio ($29), a dry red table wine from the Douro Valley that is complex and

supple and built to handle the strong flavors of smoked meats and sausages from

the grill. This wine is a blend of mostly touriga franca and touriga nacional,

with a splash of tinta amarela.

It's a beautiful wine with steak on the grill.

My second red pick for Labor Day is the juicy, suave 2010 Clos de Gilroy

($15) from Bonny Doon. This beautiful wine is 100 percent grenache, and it's a

triumph for winemaker Randall Grahm both in terms of quality and value. It is

absolutely one of the finest wines in the world at the price.

Having nicely stocked the wine cellar for my Labor Day feast, the actual work

over the grill becomes a labor of love.

Email comments to whitleyonwine@yahoo.com

and follow Robert Whitley on Twitter @wineguru.

Posted by Robert Whitley at 10:59 AM

|

|

August 28, 2012

Once upon a time — a lifetime ago, really — I adored Zinfandel, the spicy,

brambly red wine that was unique to California. Somewhere along the way,

zinfandel lost me. I don't recall the precise moment, but it could have been the

last Zinfandel Advocates and Producers (ZAP) tasting I attended at Fort Mason in

San Francisco.

Although it's been years since that event, I remember leaving in disgust.

Within an hour, most of those in attendance were bombed out of their minds after

gorging on the high-octane Zins being presented. Or so it seemed.

That was at the beginning of a creepy phase when winemakers started to

compete with each other to prove which one could grow the ripest grapes and make

the Zin with the most heft (a winemaker would correct me and insert the word

"flavor" in place of heft).

So Zinfandel and I parted company, with an exception or two. Grgich Hills

always made a balanced Zin, and it was a pleasure to assess those samples when

they came my way. In general, however, my assistant knows to check the alcohol

by volume (ABV) on Zinfandel samples and pull any that approach 16 percent. The

ABV on these wines is often much higher than the stated level because vintners

have leeway to exceed it by as much as 1.0 to 1.5 percent. Simply put, a 12.5 ABV wine

could actually come in at 14 percent, and a 16.0 ABV could go in the bottle at

17.0.

Still, I do have fond memories of what I consider the heyday of Zinfandel in

the late 1980s and early 1990s and occasionally get the urge to give Zin another

shot, so to speak.

I decided to take a chance on the 2009 St. Francis Pagani Vineyard Old Vines

Zinfandel from Sonoma Valley. I chose this particular wine because I respect the

producer and love the region. I did not check the ABV before pulling the cork.

That was a mistake.

The

St. Francis Pagani Zin tasted pretty good, no doubt about it. But the heft, the

jammy black fruit, the slight buzz I felt almost immediately all raised a red

flag. I picked up the bottle to check the alcohol. The type was so small I

couldn't read it. Even with a magnifying glass, it was difficult. I eventually

determined the ABV was a boozy 16.1 percent. The

St. Francis Pagani Zin tasted pretty good, no doubt about it. But the heft, the

jammy black fruit, the slight buzz I felt almost immediately all raised a red

flag. I picked up the bottle to check the alcohol. The type was so small I

couldn't read it. Even with a magnifying glass, it was difficult. I eventually

determined the ABV was a boozy 16.1 percent.

Now, to some that might not seem so bad. After all, we sip Port (a wine

fortified with distilled spirits) at about 20 percent ABV and think nothing of

it. We drink 80 proof vodka (40 percent ABV) and don't get sloshed unless we

drink too much.

But here's the rub. Port is typically served in small quantities following a

meal. Other than Sir Winston Churchill, who reputedly consumed a bottle of Port

every day in his later years, I know of no one who drinks Port in such quantity.

And vodka is typically mixed with other beverages, diluting the ABV to much

lower levels.

So let's do the math. Two people share a bottle of the 16.1 ABV St. Francis

Pagani Zin at dinner. Each person enjoys half the bottle, about 13.5 ounces. At

16.1 ABV, that comes out to 2.16 ounces of alcohol. A third person enjoys five

vodka & tonic cocktails, each with an ounce of vodka. That works out to 2.0

ounces of alcohol — total.

Now suppose the vodka drinker offered to drive you home. Would you rather go

with the Zin drinkers, who actually consumed more alcohol? I would like to think

you would call a taxi, instead.

Of course, everyone's body is different, and some would have the weight and

mass to imbibe at such a high level of ABV and be able to function and not go

over the legal limit for driving. Others wouldn't.

Why take the chance? That question is aimed more at the wine producer than

the wine consumer. The answer, I believe, is that some in my profession are fond

of these high-alcohol wines and give them rave reviews. This is the "gobs and

gobs of fruit" crowd, and in my humble opinion, they are playing a dangerous

game. The producers are merely making the wines that will garner the most

effective praise.

That's a dangerous game, too. Yes, these wines taste good, at least for a

time. But they weren't too shabby back in the day of 14.5 ABV. The difference

isn't what you might think — 1.5 percent. The difference between a 14.5 ABV wine

and a 16.0 ABV wine is more like 10 percent, and greater if the producer of the

16.0 wine fudges the number.

My fear is that someone who can't handle that jump in alcohol is going to get

hurt — and that an antagonism to wine in general could result. It's difficult

enough at modest levels of alcohol to manage a night on the town and drive home

safely. Why flirt with disaster?

It seems to me that it would be in the wine industry's best interest to

police itself and rein in the purveyors of these so-called fruit bombs before

someone decides to do it for them.

If nothing else, they could at least print the ABV declaration on the label

in larger type. That would be a start.

Email comments to whitleyonwine@yahoo.com

and follow Robert Whitley on Twitter @wineguru.

Posted by Robert Whitley at 9:48 AM

|

|

August 25, 2012

True confession: Most wine books bore me.

There are exceptions, of

course. For me, those tend to be the authoritative reference works written by

authors with impeccable credentials, such as Jancis Robinson, Robert M. Parker

Jr., Hugh Johnson and my good friends and colleagues Ed McCarthy, Mary

Ewing-Mulligan and Stephen Brook.

There is a new wine book loose upon

the land, "The New York Times Book of Wine" ($24.95, Sterling Publishing), and I

highly recommend it, though for reasons beyond the fact that it's simply a good

read whether you are a wine connoisseur or not.

The New York

Times Book of Wine is an anthology from the archives of The New York Times. It

represents the work of 28 different authors, including the likes of Frank Prial,

R.W. Apple Jr. and Eric Asimov, who is currently the chief wine critic at the

Times. It was edited by Howard G. Goldberg, a longtime editor at the Times and a

frequent contributor to its wine pages. The New York

Times Book of Wine is an anthology from the archives of The New York Times. It

represents the work of 28 different authors, including the likes of Frank Prial,

R.W. Apple Jr. and Eric Asimov, who is currently the chief wine critic at the

Times. It was edited by Howard G. Goldberg, a longtime editor at the Times and a

frequent contributor to its wine pages.

If you have even a passing

interest in wine, or wine and food, you will find much to like in The New York

Times Book of Wine, but that's not what I personally find most

appealing.

This book harks back to a bygone era in wine journalism,

before the rough and tumble of the Internet coarsened the dialogue on wine.

While it is true that the Internet has exposed a trove of heretofore esoteric

information on wine to those curious enough to type a few words into their

Google search function, there is little doubt this flood of information also

comes with its share of bogus commentary passing as expertise.

Not so in

the era conjured up by this new book from The Times, which, for as long as I can

remember, has covered wine with the same demanding standards of reportage that

it covers general news. Not to mention the added bonus that the Times has always

deployed serious students of wine — most of them would shy from the accusation

they are "experts" — in its wine reportage and commentary.

At one time,

many other newspapers across the land attempted to emulate the Times with their

own staff-written columns and articles on wine. That day is long gone. News hole

and staff resources have been shrinking at daily newspapers for more than a

decade. The newspaper wine columnist is a dying breed in most U.S.

cities.

The New York Times Book of Wine is not only a reminder, but

gives historical context to the period when wine journalism, as practiced by

newspapers, was at its peak.

Posted by Robert Whitley at 4:38 PM

|

|

August 19, 2012

As the summer heat builds and meals trend toward light, fresh ingredients, I am always drawn to the intriguing white wines of southern Italy, made from obscure grape varieties known and grown only in the hot, dry Mediterranean climate where they have thrived for centuries.

The whites of Italy's southern provinces have weight and complexity without being heavy. They are made to be consumed with food. The alcohol levels are modest despite the warm growing season. And, best of all, prices have been held in check because demand is limited primarily to those adventurous souls who are brave enough to try something different. The whites of Italy's southern provinces have weight and complexity without being heavy. They are made to be consumed with food. The alcohol levels are modest despite the warm growing season. And, best of all, prices have been held in check because demand is limited primarily to those adventurous souls who are brave enough to try something different.

Exhibit A would be Donnafugata Anthilia, a blend of ansonica and catarratto grapes grown in western Sicily, near the ancient village of Marsala. Move to the head of the class if you've ever heard of either grape. Donnafugata was founded by Giacomo and Gabriela Rallo nearly 30 years ago, and it has been one of Sicily's most respected wineries since opening its doors. Anthilia was the first wine ever made at Donnafugata.

It is one of a handful of Italian whites I enjoy springing on unsuspecting houseguests. Few have ever heard of it, let alone tasted it, and the typical reaction upon the first sip is utter amazement. It is well balanced, tastes predominantly of yellow peaches, and is silky and refined. I enjoy it with steamed mussels, squid and various marinated summer vegetables.

Average retail price at WineSearcher.com: $13. Hard to believe a wine so good costs so little.

Exhibit B is the Feudi di San Gregorio Falanghina, a wine that is 100 percent varietal, made from grapes grown in the Sannio district in the Campania region, not far from Naples. The vineyards are planted on hillsides at elevations ranging from 700 to 1,300 feet above sea level. The elevation and cool, clay soils contribute to the freshness of this wine.

The flavor profile is a subtle mix of tropical fruits, apple and citrus, with a strong essence of minerality. Though it has long been considered the poor cousin of Campania's two more renowned white wines — Greco di Tufo and Fiano di Avellino — falanghina from Feudi di San Gregorio has altered that perception somewhat.

Average retail price at WineSearcher.com: $16. And worth every penny.

Exhibit C is the exotic Feudo Principi di Butera Insolia, a wine that is also 100 percent varietal, made from the grape known as insolia in some parts of Sicily, ansonica in others.

Butera is a small village in the southeastern corner of Sicily, halfway between the ancient Greek ruins of Agrigento and the ancient city of Ragusa. This is a mineral-driven white with an intensely floral nose, but subdued fruit aromas both on the nose and palate. Butera is a small village in the southeastern corner of Sicily, halfway between the ancient Greek ruins of Agrigento and the ancient city of Ragusa. This is a mineral-driven white with an intensely floral nose, but subdued fruit aromas both on the nose and palate.

It is bone dry, perfect with steamed shellfish, grilled octopus and other fish, or all manner of Mediterranean tapas. This wine is well balanced, and the alcohol is modest at 13 percent.

Average retail price at WineSearcher.com: $13. If you get lucky, you might even find it for under $10.

Of course, these three barely scratch the surface. Italy is awash in refreshing white wines that will quench your thirst on a warm summer day. The diversity of Italian white wine is astonishing.

Besides the ubiquitous pinot grigio (best from the Alto Adige and Friuli regions), other Italian whites to tempt your taste buds might include a crisp Orvieto from Umbria, a slightly tart wine made from the ancient grechetto grape; a light and refreshing Gavi from Piemonte, made from the noble cortese grape; or a soft and voluptuous soave from the Veneto, which is made primarily from the garganega grape.

Although few of these wines or grape varieties are household terms in most households, they are sure to deliver unique taste experiences you won't soon forget. And that is a beautiful thing.

Posted by Robert Whitley at 11:10 AM

|

|

August 13, 2012

We are delighted to announce the expansion of Wine Review Online’s all-star lineup of contributors with the addition of Rebecca Murphy and James Tidwell MS. Rebecca and James will be reviewing wines on a regular basis, and you should also watch for pieces by them in the WRO blog space. They are among the most highly respected wine professionals in the United States, and indeed both have earned international reputations over the years.

The first set of reviews from Rebecca and James will appear on WRO’s “Reviews” page this Wednesday, August 15. You’ll find their names linked to each of their reviews, as is always the case on WRO, which never runs a review or a point score without explicitly indicating the author. And by the way, if you haven’t noticed already, each of our reviewers writes with a distinctive voice based on an independent but highly trained palate. There’s no “party line” at Wine Review Online, which operates on a very simple editorial model: Engage the very best tasters and writers, and then let them do their own thing.

As you’ll soon see, Rebecca and James definitely fit that bill, and we couldn’t be more pleased to provide a forum for their outstanding talents. Here are brief biographical sketches that will provide an indication of their accomplishments…but only an indication, as their full CVs are far too extensive to reproduce here:

Rebecca Murphy was the first female wine steward in Texas, and has gone on to found and  produce The Dallas Morning News and TexSom Wine Competition. She is also handling the operations for the newly established Sunset International Wine Competition, and has judged many national and international wine competitions. As a writer, she has contributed a weekly feature to The Dallas Morning News for many years, and has written for Wine Business Monthly and Wines & Vines in addition to furnishing entries for The Oxford Companion to Wine and the sixth edition of The World Atlas of Wine. produce The Dallas Morning News and TexSom Wine Competition. She is also handling the operations for the newly established Sunset International Wine Competition, and has judged many national and international wine competitions. As a writer, she has contributed a weekly feature to The Dallas Morning News for many years, and has written for Wine Business Monthly and Wines & Vines in addition to furnishing entries for The Oxford Companion to Wine and the sixth edition of The World Atlas of Wine.

James Tidwell, MS, CWE, is currently Beverage Manager and Sommelier at Four Seasons  Resort and Club in Irving, Texas. He is a sommelier representative on Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts’ core wine committee, and is the Lead Sommelier on the corporate beverage committee. In 2009, he passed the prestigious Master Sommelier examination, and in 2003 passed the Certified Wine Educator Exam on the first attempt, earning the highest score out of the hundreds of candidates who took the exam that year. James is also the co-founder of TEXSOM, North America’s preeminent wine educational conference. Resort and Club in Irving, Texas. He is a sommelier representative on Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts’ core wine committee, and is the Lead Sommelier on the corporate beverage committee. In 2009, he passed the prestigious Master Sommelier examination, and in 2003 passed the Certified Wine Educator Exam on the first attempt, earning the highest score out of the hundreds of candidates who took the exam that year. James is also the co-founder of TEXSOM, North America’s preeminent wine educational conference.

Posted by Michael Franz at 3:51 PM

|

|

August 9, 2012

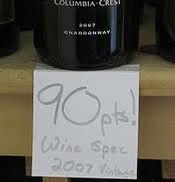

The value of wine ratings, particularly those that provide numerical scores based upon the 100-point scale, is a frequent subject of debate among those who critically evaluate new wine releases and make recommendations to consumers.

In recent years, there has been a loud, and sometimes vulgar, attempt to discredit the 100-point scale, which is used by WRO and virtually all of the major wine publications to provide an easy-to-understand quantification of wine quality. You don't have to be a master sommelier to figure out that a reviewer gave the wine an A+ grade if it was assigned a score of 95 points or higher.

This system has served the consumer well over the 30 years or so since it was introduced by one of the wine mags, and popularized by the infamous wine critic, Robert Parker. This system has served the consumer well over the 30 years or so since it was introduced by one of the wine mags, and popularized by the infamous wine critic, Robert Parker.

Still, there are those who loathe it for a variety of reasons. The most oft-repeated criticism is that it is impossible to assign a number to a bottle of wine. What is the difference, the argument goes, between an 88-point wine and a 92-point wine? Who could possibly be that precise?

Indeed, how do we explain that WRO assigned a 92-point score when a popular wine magazine gave the same wine 88 points? Which is it? This gets to my personal point of view that the score is merely a measure of a specific wine critic's enthusiasm for the wine being reviewed.

What's important is that the critic is consistent and can repeat the analysis in a blind tasting. So it was gratifying to me that when, earlier this year, I was given the same wines twice while tasting "blind" at the Concours Mondial de Bruxelles, the world's largest international wine competition, I was able to virtually repeat my score on the two wines used to test my "repeatability."

The Concours Mondial just so happens to use the 100-point scale. I gave the first wine that was put to me twice a score of 86, then followed with an 87 when, unbeknownst to me, it was presented a second time. The second wine rated an 89-point score on the first tasting; 90 points when it came around again.

The results of the repeatability test only strengthened my resolve to resist the pressure from some quarters to renounce the 100-point scale in favor of what I consider a bland format that lumps wines inside broad, non-controversial categories such as "recommended" or "highly recommended." To me, that's a wimpy, gutless option.

When I tag a wine 97 points, on the other hand, it's a bold statement certain to get your attention. And it leaves no doubt that I'm crazy about the wine.

Over the years, whether speaking to consumers at a public tasting or simply making generalized wine suggestions around the holidays, I've learned there is one question that is paramount when I've thrown out a bevy of suggestions: Which wine do I like best?

The 100-point scale is the most precise tool for sorting out those levels of preference.

The reason that is so important is because most wine drinkers are not hip to every new wine that comes along; and there are literally millions of new wine releases every vintage. The options can be overwhelming even for those who have the energy and time to attend tastings and do the research. The average person is more than happy to let someone else do the homework and issue a grade, or score, that can be used as a guide when shopping, particularly in a venue that provides a vast selection and little assistance from knowledgeable staff. The reason that is so important is because most wine drinkers are not hip to every new wine that comes along; and there are literally millions of new wine releases every vintage. The options can be overwhelming even for those who have the energy and time to attend tastings and do the research. The average person is more than happy to let someone else do the homework and issue a grade, or score, that can be used as a guide when shopping, particularly in a venue that provides a vast selection and little assistance from knowledgeable staff.

I was appalled recently when a colleague who opposes the 100-point scale tweeted words to the effect that anyone who would buy a wine based upon a numerical rating is a troglodyte.

No, I believe the caveman in the crowd is the person so steeped in the wine-geek's view of the world that he or she would begrudge ordinary folk this simple tool that cuts through all the pretentious and often confusing wine-speak you will find in most wine reviews, including my own.

Posted by Robert Whitley at 11:22 AM

|

|

|

|